Many of us are familiar with the five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. But where does this idea come from?

Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, one of the first psychiatrists to study the end-of-life, developed the 5-stage model after interviewing individuals with terminal illness. Using qualitative analysis, she combed through the interviews and identified common themes. Her findings were published first in a 1969 issue of LIFE magazine (original photocopy here1) and then in her influential book On Death and Dying. It shone a light on the voices of the terminally ill and importantly served as an educational tool to help medical professionals understand end-of-life concerns. Physicians at the time (and arguably sometimes now) weren’t trained to attend to the psychological aspects of disease. It helped to usher in the hospice and palliative care movement, which focuses on patient comfort in terms of attending to physical, emotion, and spiritual pain rather than solely on life-extension as the only goal.

Criticisms of the 5-stage model

Little did I know what a hotly debated topic I walked into when I started researching for this article! Despite being so well-known, the 5-stage model has been critiqued for several reasons.

First, the model was extrapolated from the dying to the bereaved. Participants in the original interviews were grieving their own impending deaths, which seems like a key detail. Does grieving one’s own life translate to how we grieve the loss of others? In this way, the model is really one of anticipatory grief. What happens after the death occurs? We’ll of course never know from the ones who passed themselves, but what about the rest of us who are left behind? In this way, it doesn’t truly help us know what happens in the aftermath of loss or capture additional stages that have been proposed, such as yearning or making meaning.

Psychologists and grief researchers have highlighted that the model is not empirically supported by quantitative data. Even though these emotional states do occur for many grieving people, not everyone experiences all of these stages, and not in a linear order. Further, the model is “descriptive” not “prescriptive”, meaning that it reflects the content of what people commonly experienced but is by no means the only or “right” way to go about it.

I was surprised to learn about such controversy over the 5-stage model, including some pretty harshly worded academic articles (one article even goes as far as to say it should be “relegated to the realms of history”). Academics expressed concerns not only about the accuracy, but also about potential harms of the 5-stage model. Namely, that if one’s experience does not cleanly follow the stages of grief, or if one continues to grieve for an extended period of time, they may feel as if they are doing it “wrong” - or worse, that there is something wrong with them.2

Why has the 5-stage model persisted in popular memory?

If this model has flaws, why has it hung around? I’m personally not particularly interested in tearing it down, as much as I am in why its appeal has caused it to persist in collective consciousness.

A professor in grad school told me, “A model is only good insofar as it is useful.” Basically, no theory is perfect. No model can exactly capture all of the nuance and variability in human experience. But a good model can help us make sense of our experience, organize us, and validate what we are going through. The commonalities can make us feel less alone and provide a roadmap for what to expect.

There’s an appeal of having an instruction manual, or at least a guide of what’s to come. It gives us clarity and comfort. A linear roadmap, especially for those of us in Western culture, is even better! Why has this model persisted in cultural popularity? Holland & Neimeyer (2010) propose that part of the appeal of the 5-stage model of grief is because it follows the trajectory of the hero.

Cue 9th grade English class. Just like in comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell3’s heroic cycle, the hero (the bereaved) encounters a challenge (the death), which they must go on a quest to overcome. They go through clear steps of trials and tribulations (the stages of grief). They emerge victorious, to a state where they are “done” grieving and arrive at acceptance. There’s a problem; it gets solved. If only it could be that simple. In reality, grief is not something that be conquered or goes away.

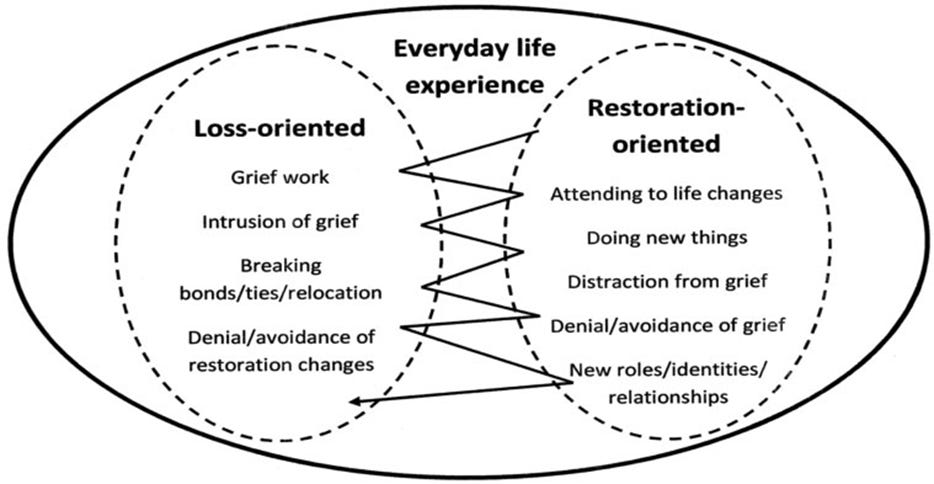

Dual Process Model

What other models exist?4 There have been many other ways of understanding grief (summarized briefly here). I could spend many posts going through each one, and maybe I will! I’ll start with one of the most prominent newer models that attempts to explain the process of simultaneously grieving a loss and figuring out what’s next: The Dual Process Model.

The Dual Process Model proposes that grieving involves a non-linear, continuous, ping-ponging back and forth between 1) loss-oriented and 2) restoration-oriented tasks. I generally think of loss-oriented as reflecting on the past and directly feeling grief, whereas restoration-oriented is focused on the future and adapting to the new realities of ongoing life. The dual process model says that it’s actually healthy to spend some time not looking back or immersing one’s self in “grief work” all the time. We need breaks. It’s even okay to avoid at times and do new and different things.

This oscillation back and forth between directly being inside of the pool of grief and then getting out of the pool to dry off and go about your daily life of work and tending to relationships and maybe even trying to have some fun…. it’s definitely resonant. Although I admit that in comparison to the 5-stage model, the dual process model does seem a bit more dense and complex. It’s…messy. What does this model actually mean in daily life and how can it be used?

For answers to these questions and more, stay tuned for my *first podcast episode* in the near future where I interview Dr. Saren Seeley, who researches the neuroscience of grief and earned her Ph.D. in clinical psychology from the University of Arizona under the mentorship of Dr. Mary-Frances O’Connor (the author of The Grieving Brain, which I’ve been fan-girling about).

Metaphors for grieving & healing:

There are probably a million different models for grief. Metaphors are models. I’ll leave you with some that I’ve thought of or resonated with:

Water: too much or too little of it. It really does come on like tidal waves, flash floods, or gentle currents. Or it can leave you feeling thirsty and dehydrated.

A plant who was deprived of water. My Schefflera had one main stalk whose leaves turned brown and fell off. But when I pruned and watered it, it started to regrow new green leaves in the offshoots.

A lizard who lost its tail. Some kinds of lizards can regrow it, whereas others can’t. For those who can regenerate, the new tail will never be exactly the same as it was.

A time machine that catapults you back in time in a split second. Like when I bit into a crispy piece of bacon and the sense memory immediately hit me with tears.

The seasons folding into the next, cyclical and constantly changing. Seeking to be connected to nature, I recently started Motherwort + Rose’s year-long class about creativity and grieving with the seasons. I typically think of grief as being most like winter: dormant, low-energy, and isolated. But it’s been interesting to realize how grief for me can also feel urgent and be full of movement, like the new restless energy of Spring.

In an amazing episode of Anderson Cooper’s podcast All There Is, Steven Colbert likens grief to:

“The loss of the exchange of love. There is a food that’s exchanged there. And grief is like starving.”

“The pain will change like wine into something else. Can change into wisdom about human experience that you can share with other people.”

Please let me know your metaphors for grief or healing. Thank you as always for reading.

I highly recommend time-traveling back to the year 1969 by checking out the photocopy of LIFE. Plentiful ads for cigarettes, whiskey, televisions encased in gorgeous ornate wooden boxes, and watches for your wife! Articles on the moon landing, Jesse Jackson, police brutality, protests against the Vietnam War, and famed Ohio State University’s football coach Woody Hayes. My dad was an OSU fan and personally knew Neil Armstrong, so this felt synchronistic.

It seems like the 5-stage model has taken on a life of its own, as Kübler-Ross herself said she never intended it to be interpreted as how-to-grieve rules. She has also acknowledged that the emotions corresponding to the stages can be experienced simultaneously or within a matter of moments, and that no one stage is necessarily better or more enlightened than another (that’s right, not even acceptance). As you might be able to tell, I still find myself having a soft spot for Kübler-Ross because of her attention to the topic of dying and in my opinion a net-positive impact on end-of-life healthcare.

Joseph Campbell incidentally died of the same type of cancer (esophageal) as my father.

I wish to contextualize that these models are from a Western psychological science lens, which is where my educational background positions me at this point in time, at least to start. There are many other valuable ways to understand grief, including psychoanalytic, spiritual, religious, collective, artistic, and beyond.